An interview with Everett Epstein, BVP High School Teacher of the Year

Why did you choose teaching as a career? Were there defining moments in your

life that inspired you to do so?

Fittingly, one of the books I’m reading right now asks this question in the title: Why Teach? by Mark Edmundson. His answer: the humanities classroom offers one of the last authentic spaces for a kind of disruptive thinking, one that unsettles a student’s passivity and upsets ease. To teach is to push against the ideological conscriptions of consumption, to administer the pharmakon. In general, my own teaching philosophy adheres to Edmundson’s vision — education, when done well, feels authentically disruptive — but I don’t think he fully accounts for the radically humbling experience on the end of teachers. That is, I feel like I initially directed myself towards Edmundson’s ideal in college, which I coupled with a novel political leftism, and then discovered that a more honest reason behind my pursuit lay in the desire to upend an unearned, wrong-headed confidence that had become increasingly oppressive. Teaching both spoke to this ego and undid it; it delivered both poison and antidote.

Fittingly, one of the books I’m reading right now asks this question in the title: Why Teach? by Mark Edmundson. His answer: the humanities classroom offers one of the last authentic spaces for a kind of disruptive thinking, one that unsettles a student’s passivity and upsets ease. To teach is to push against the ideological conscriptions of consumption, to administer the pharmakon. In general, my own teaching philosophy adheres to Edmundson’s vision — education, when done well, feels authentically disruptive — but I don’t think he fully accounts for the radically humbling experience on the end of teachers. That is, I feel like I initially directed myself towards Edmundson’s ideal in college, which I coupled with a novel political leftism, and then discovered that a more honest reason behind my pursuit lay in the desire to upend an unearned, wrong-headed confidence that had become increasingly oppressive. Teaching both spoke to this ego and undid it; it delivered both poison and antidote.

I remember attending a lecture from Christopher Edley Jr., former dean at Berkeley Law, who spoke on American education in college. Over the course of the Q & A, I became increasingly certain that this issue was my calling. I also remember being coached during a summer fellowship at Uncommon, and having to conclude that I was often offensively bad at Teach Like a Champion techniques — embarrassingly unable to develop radar in a class of three, inept at Cold Call and Turn & Talks. This is all to say, the profession has, like any worthy craft, offered both glimpses of inspiration and disarmingly difficult challenge. To both feel animated by its potential, in which both Edley Jr. and Edmundson believe, and paralyzed by it’s daunting enormity — this dilemma makes the career worthwhile, vital, and ever-changing.

Why Blackstone Valley Prep?

Much of my teaching philosophy, in the abstract, has been shaped by Richard Rorty’s Achieving Our Country, which admits that America requires a continuous reassertion of — and reorientation towards — its ideals. BVP’s vision of integration, one that recognizes Rhode Island’s built and legislated inequalities, imagines an American future that redistributes opportunity across townships. Practice desegregation in New England, contending with past and present calls from white families to divest from diverse public schools — this cause strikes me as a patriotic one, an imperative that citizenship dictates.

On a less serious note, BVP’s scholars consistently surprise me with their level of commitment to each other and their communities. Whenever I cede the floor to a conversation about class, race, or gender in reference to our text, I’m amazed at the depth and felicity of their perspectives. Few students in the state (and indeed the nation) can engage with a discourse on integration with as much authority. I’m immensely grateful to teach such students and work with parents who have committed themselves annually to this vision, to these ideals, whether consciously or unconsciously.

What can you share with others about your classroom? What can students expect when they take your class?

Students can expect to grow, both emotionally and academically over the course of my class. They can expect to struggle, but through their struggle, they can expect to develop practice writing skills. They can expect to laugh and find joy in literature. They can expect to discuss their country, its history, and their own perspectives on the contemporary moment. They can expect to have their voice respected and heard and challenged. They can expect to listen to my perspective on the novels we read, but only in preparation for the elevation of their own perspectives. Most importantly, they can expect to hear, read, and revise every single voice in their class because entering my classroom means entering a community.

Tell us about one of your favorite moments in the classroom.

One of my favorite moments from the classroom came last week when my AP Literature group entered a Socratic Seminar on Alice Munro’s “Runaway” armed only with a cursory understanding of Critical Lenses. They intuitively found connections across Marxist critique and Psychoanalysis before deftly applying a feminist perspective to the deceptively difficult text. It confirmed for me how hungry scholars are to read through an academic perspective, but also how their lived experience easily informed a nascent love of theory. I found myself not only impressed, but inspired to set up more frequent discussions uses this same frame.

What are you reading now?

I have a couple books going right now: At the Existentialist Café by Sara Bakewell, Why Teach? by Mark Edmundson, We the Animals by Justin Torres, and McGlue by Ottessa Moshfegh. On audiobook, I’m listening to The Snowman by Jo Nesbø, The Passage of Power by Robert Caro, and The Spy Who Came in from the Cold by John Le Carré. I’m also about to jump into a writing course on Anne Carson’s poetry, which will be another book to add to my list.

Are there best practices that you implement in your classrooms that you’d like to share with other high school ELA teachers?

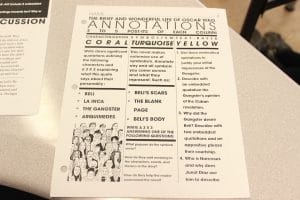

I have a few teaching texts that I frequently return to whenever I come across a class issue. Kelly Gallagher’s Deeper Reading and Donald Mcquade’s Seeing and Writing 4 spring to mind; but honestly, the best practices that I’ve received come from designing and writing in classes outside of BVP. Many of my “Art of the Sentence” workshopping derives from building tools (be it pedagogy die or a color-coding system) during the AP Summer Institute, RISD CE courses, or Frequency Writing Workshops. I have begun to challenge myself to design something new whenever I have a training — something that I can show to students. As a result, I find myself held accountable in a way that elevates potentially tired PPT presentations or PD sessions. If I’m on Illustrator or InDesign making a tool, I feel engaged in much the way we want our students to feel engaged.

Everett grew up in Alexandria, VA, is a Brown University alum, and has been an educator for 4 years.